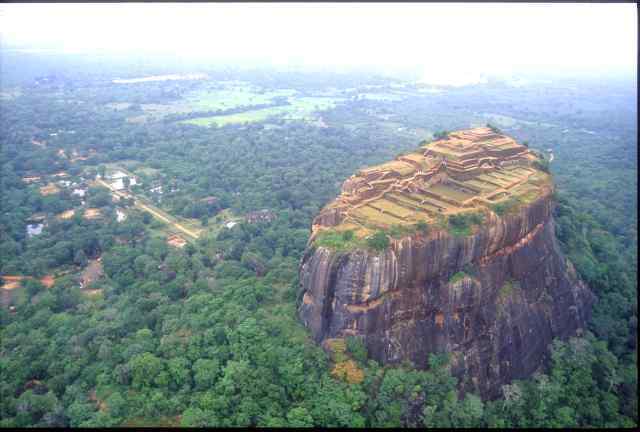

Sigiriya (Lion Rock,

Sinhala:

සීගිරිය, pronounced see-gee-REE-yah

Tamil:

சிகிரியா) is located in the central

Matale District of the

Central Province,

Sri Lanka.

The name refers to a site of historical and archeaological significance

that is dominated by a massive column of rock nearly 200 metres

(660 ft) high. According to the ancient Sri Lankan chronicle the

Culavamsa the site was selected by King

Kasyapa

(477 – 495 CE) for his new capital. He built his palace on the top of

this rock and decorated its sides with colourful frescoes. On a small

plateau about halfway up the side of this rock he built a gateway in the

form of an enormous lion. The name of this place is derived from this

structure —Sīhāgiri, the Lion Rock. The capital and the royal palace

were abandoned after the king's death. It was used as a Buddhist

monastery until the 14th century.

[1]

Sigiriya today is a UNESCO listed

World Heritage Site. It is one of the best preserved examples of ancient urban planning.

[2] It is the most visited historic site in Sri Lanka.

[3]

History

Environment around the Sigiriya may have been inhabited since

prehistoric times. There is clear evidence that the many rock shelters

and caves in the vicinity were occupied by Buddhist monks and ascetics

from as early as the 3rd century BCE.

In 477 CE, prince Kashyapa seized the throne from King Dhatusena,

following a coup assisted by Migara, the king’s nephew and army

commander. Kashyapa, the king’s son by a non-royal consort, usurped the

throne from the rightful heir,

Moggallana, who fled to

South India. Fearing an attack from Moggallana, Kashyapa moved the capital and his residence from the traditional capital of

Anuradhapura

to the more secure Sigiriya. During King Kashyapa’s reign (477 to 495

CE), Sigiriya was developed into a complex city and fortress.

[4][5]

Most of the elaborate constructions on the rock summit and around it,

including defensive structures, palaces, and gardens, date back to this

period.

Kashyapa was defeated in 495 CE by Moggallana, who moved the capital

again to Anuradhapura. Sigiriya was then turned into a Buddhist

monastery, which lasted until the 13th or 14th century. After this

period, no records are found on Sigiriya until the 16th and 17th

centuries, when it was used briefly as an outpost of the

Kingdom of Kandy.

The Culavamsa describes King Kashyapa as the son of King

Dhatusena. Kashyapa murdered his father by walling him up alive and then usurping the throne which rightfully belonged to his brother

Mogallana, Dhatusena's son by the true queen. Mogallana fled to

India

to escape being assassinated by Kashyapa but vowed revenge. In India he

raised an army with the intention of returning and retaking the throne

of Sri Lanka which he considered to be rightfully his. Knowing the

inevitable return of Mogallana, Kashyapa is said to have built his

palace on the summit of Sigiriya as a fortress and pleasure palace.

Mogallana finally arrived and declared war. During the battle Kashyapa's

armies abandoned him and he committed suicide by falling on his sword.

Chronicles and lore say that the battle-elephant on which Kashyapa

was mounted changed course to take a strategic advantage, but the army

misinterpreted the movement as the King having opted to retreat,

prompting the army to abandon the king altogether. It is said that being

too proud to surrender he took his dagger from his waistband, cut his

throat, raised the dagger proudly, sheathed it, and fell dead.

Moggallana returned the capital to Anuradapura, converting Sigiriya into

a monastery complex.

[6]

Alternative stories have the primary builder of Sigiriya as King

Dhatusena, with Kashyapa finishing the work in honour of his father.

Still other stories have Kashyapa as a playboy king, with Sigiriya a

pleasure palace. Even Kashyapa's eventual fate is uncertain. In some

versions he is assassinated by poison administered by a concubine; in

others he cuts his own throat when isolated in his final battle.

[7]

Still further interpretations have the site as the work of a Buddhist

community, with no military function at all. This site may have been

important in the competition between the

Mahayana and

Theravada Buddhist traditions in ancient Sri Lanka.

The earliest evidence of human habitation at Sigiriya was found from

the Aligala rock shelter to the east of Sigiriya rock, indicating that

the area was occupied nearly five thousand years ago during the

Mesolithic Period.

Buddhist monastic settlements were established in the western and

northern slopes of the boulder-strewn hills surrounding the Sigiriya

rock, during the 3rd century BCE. Several rock shelters or caves were

created during this period. These shelters were made under large

boulders, with carved drip ledges around the cave mouths.

Rock inscriptions

are carved near the drip ledges on many of the shelters, recording the

donation of the shelters to the Buddhist monastic order as residences.

These were made within the period between the 3rd century BCE and the

1st century CE.

Archaeological remains and features

The Lion Gate and Climbing Stretch

In 1831 Major

Jonathan Forbes

of the 78th Highlanders of the British army, while returning on

horseback from a trip to Pollonnuruwa, came across the "bush covered

summit of Sigiriya".

[8]

Sigiriya came to the attention of antiquarians and, later,

archaeologists. Archaeological work at Sigiriya began on a small scale

in the 1890s. H.C.P. Bell was the first archaeologist to conduct

extensive research on Sigiriya. The Cultural Triangle Project, launched

by the

Government of Sri Lanka,

focused its attention on Sigiriya in 1982. Archaeological work began on

the entire city for the first time under this project. There was a

sculpted lion's head above the legs and paws flanking the entrance, but

the head broke down many years ago.

Sigiriya consists of an ancient castle built by King Kashyapa during

the 5th century. The Sigiriya site has the remains of an upper palace

sited on the flat top of the rock, a mid-level terrace that includes the

Lion Gate and the mirror wall with its frescoes, the lower palace that

clings to the slopes below the rock, and the

moats, walls, and gardens that extend for some hundreds of metres out from the base of the rock.

The site is both a palace and a fortress. The upper palace on the top

of the rock includes cisterns cut into the rock that still retain

water. The moats and walls that surround the lower palace are still

exquisitely beautiful.

[9]

Close up of the Lions Paw

Site plan

Sigiriya are considered one of the ismost important urban planning sites of the first millennium, and the

site plan

is considered very elaborate and imaginative. The plan combined

concepts of symmetry and asymmetry to intentionally interlock the

man-made geometrical and natural forms of the surroundings. On the west

side of the rock lies a park for the royals, laid out on a symmetrical

plan; the park contains water-retaining structures, including

sophisticated surface/subsurface hydraulic systems, some of which are

working even today. The south contains a man-made reservoir; these were

extensively used from the previous capital of the dry zone of Sri Lanka.

Five gates were placed at entrances. The more elaborate western gate is

thought to have been reserved for the royals.

[10][11]

Frescoes

John Still in 1907 suggested, "The whole face of the hill appears to

have been a gigantic picture gallery... the largest picture in the world

perhaps".

[12]

The paintings would have covered most of the western face of the rock,

an area 140 metres long and 40 metres high. There are references in the

graffiti to 500 ladies in these paintings. However, most have been lost

forever. More frescoes, different from those on the rock face, can be

seen elsewhere, for example on the ceiling of the location called the

"Cobra Hood Cave".

Although the frescoes are classified as in the

Anuradhapura period, the

painting style is considered unique;

[13]

the line and style of application of the paintings differing from

Anuradhapura paintings. The lines are painted in a form which enhances

the sense of volume of the figures. The paint has been applied in

sweeping strokes, using more pressure on one side, giving the effect of a

deeper colour tone towards the edge. Other paintings of the

Anuradhapura period contain similar approaches to painting, but do not

have the sketchy lines of the Sigiriya style, having a distinct artists'

boundary line. The true identity of the ladies in these paintings still

have not been confirmed. There are various ideas about their identity.

Some believe that they are the wives of the king while some think that

they are women taking part in religious observances. These pictures have

a close resemblance to some of the paintings seen in the

Ajanta caves in

India

The Mirror Wall

The Mirror Wall and spiral stairs leading to the frescoes

Originally this wall was so well polished that the king could see

himself whilst he walked alongside it. Made of a kind of porcelain, the

wall is now partially covered with verses scribbled by visitors to the

rock. Well preserved, the mirror wall has verses dating from the 8th

century. People of all types wrote on the wall, on varying subjects such

as love, irony, and experiences of all sorts. Further writing on the

mirror wall now has been banned for the protection of old writings of

the wall.

Dr

Senerat Paranavitana, an eminent Sri Lankan archaeologist, deciphered 685 verses written in the 8th, 9th and 10th centuries CE on the mirror wall.

[14]

One such poem in Sinhala is:

- "බුදල්මි. සියොවැ ආමි. සිගිරි බැලිමි. බැලු බැලු බොහො දනා ගී ලීලුයෙන් නොලීමි."

The rough translation is: "I am Budal [the writer's name]. (I) Came

alone to see Sigiriya. Since all the others wrote poems, I did not!" He

has left an important record that Sigiriya was visited by people

beginning a very long time ago.

The gardens

The Gardens of the Sigiriya city are one of the most important

aspects of the site, as it is among the oldest landscaped gardens in the

world. The gardens are divided into three distinct but linked forms:

water gardens, cave and boulder gardens, and terraced gardens.

The water gardens

A pool in the garden complex

The water gardens can be seen in the central section of the western

precinct. Three principal gardens are found here. The first garden

consists of a plot surrounded by water. It is connected to the main

precinct using four causeways, with gateways placed at the head of each

causeway. This garden is built according to an ancient garden form known

as

char bagh, and is one of the oldest surviving models of this form.

The second contains two long, deep pools set on either side of the

path. Two shallow, serpentine streams lead to these pools. Fountains

made of circular limestone plates are placed here. Underground water

conduits supply water to these fountains which are still functional,

especially during the rainy season. Two large islands are located on

either side of the second water garden. Summer palaces are built on the

flattened surfaces of these islands. Two more islands are located

farther to the north and the south. These islands are built in a manner

similar to the island in the first water garden.

The gardens of Sigiriya, as seen from the summit of the Sigiriya rock

The third garden is situated on a higher level than the other two. It

contains a large, octagonal pool with a raised podium on its northeast

corner. The large brick and stone wall of the citadel is on the eastern

edge of this garden.

The water gardens are built symmetrically on an east-west axis. They

are connected with the outer moat on the west and the large artificial

lake to the south of the Sigiriya rock. All the pools are also

interlinked using an underground conduit network fed by the lake, and

connected to the moats. A miniature water garden is located to the west

of the first water garden, consisting of several small pools and

watercourses. This recently discovered smaller garden appears to have

been built after the Kashyapan period, possibly between the 10th and

13th centuries.

The boulder gardens

The boulder gardens consist of several large boulders linked by

winding pathways. The gardens extend from the northern slopes to the

southern slopes of the hills at the foot of Sigiris rock. Most of these

boulders had a building or pavilion upon them; there are cuttings that

were used as footings for brick walls and beams.it is a vital component

of the spite.

The terraced gardens

The terraced gardens are formed from the natural hill at the base of

the Sigiriya rock. A series of terraces rises from the pathways of the

boulder garden to the staircases on the rock. These have been created by

the construction of brick walls, and are located in a roughly

concentric plan around the rock. The path through the terraced gardens

is formed by a limestone staircase. From this staircase, there is a

covered path on the side of the rock, leading to the uppermost terrace

where the lion staircase is situated.

Image gallery

-

-

View of one of the pools in the garden complex

-

The Sigiriya Rock seen from the Fountain Gardens

-

Rock shelters at the foot of the Sigiriya rock

-

A partially man-made shelter with brick walls, using a large boulder as the roof

-

Ruins of the Lion's mouth

-

Remains of the indents in the rock where the stairway to the top was built

-

-

The terrace below the mirror wall

-

View from the side of the Mirror wall

-

-

View over the gardens from the summit

-

Other

References

- Jump up ^ Ponnamperuma, Senani (2013). The Story of Sigiriya. Panique Pty Ltd. ISBN 9780987345110.

- Jump up ^ Bandaranayake, Senake (2005). Sigiirya City Palace Gardens Monasteries Painting. Central Cultural Fund. ISBN 9556311469 .

- Jump up ^ 2011 Research & International Relations Division Sri Lanka Tourism Development Authority Annual Statistical Report. Colombo: Research & International Relations Division. 2011. p. 58.

- Jump up ^ Ponnamperuma, Senani (2013). The Story of Sigiriya. Panique Pty Ltd. ISBN 9780987345110.

- Jump up ^ Bandaranayake, Senake (2005). Sigiirya City Palace Gardens Monasteries Painting. Central Cultural Fund. ISBN 9556311469 .

- Jump up ^ Geiger, Wilhelm. Culavamsa Being The More Recent Part Of Mahavamsa 2 Vols, Ch 39. 1929

- Jump up ^ "The Sigiriya Story". Asian Tribune. Retrieved 2006-11-24.

- Jump up ^ Forbes, Jonathan. Eleven Years in Ceylon. London: Richard Benley, 1841.

- Jump up ^ "Sri Lanka: Slip Into Antiquity". The Epoch Times. Retrieved 2005-05-04.

- Jump up ^ "Sigiriya - The fortress in the sky". Sunday Observer. Retrieved 2004-10-10.

- Jump up ^ "Sigiriya: the most spectacular site in South Asia". Sunday Observer. Retrieved 2006-08-03.

- Jump up ^ Senake Bandaranayake and Madhyama Saṃskr̥tika Aramudala. Sigriya. 2005, page 38

- Jump up ^ "Sigiriya Frescoes, Sri Lanka". Retrieved 11 December 2013.

- Jump up ^ [S.

Paranavitana, Sigiri Graffiti. Being Sinhalese verses of the eighth,

ninth and tenth centuries, 2 vols. London: Oxford University Press, for

the Archaeological Survey, Ceylon, 1956.]

- Jump up ^ Ponnamperuma, Senani. "About Sigiriya". The Story of Sigiriya. Panique Pty Ltd. Retrieved 9 March 2013.

Further reading

External links